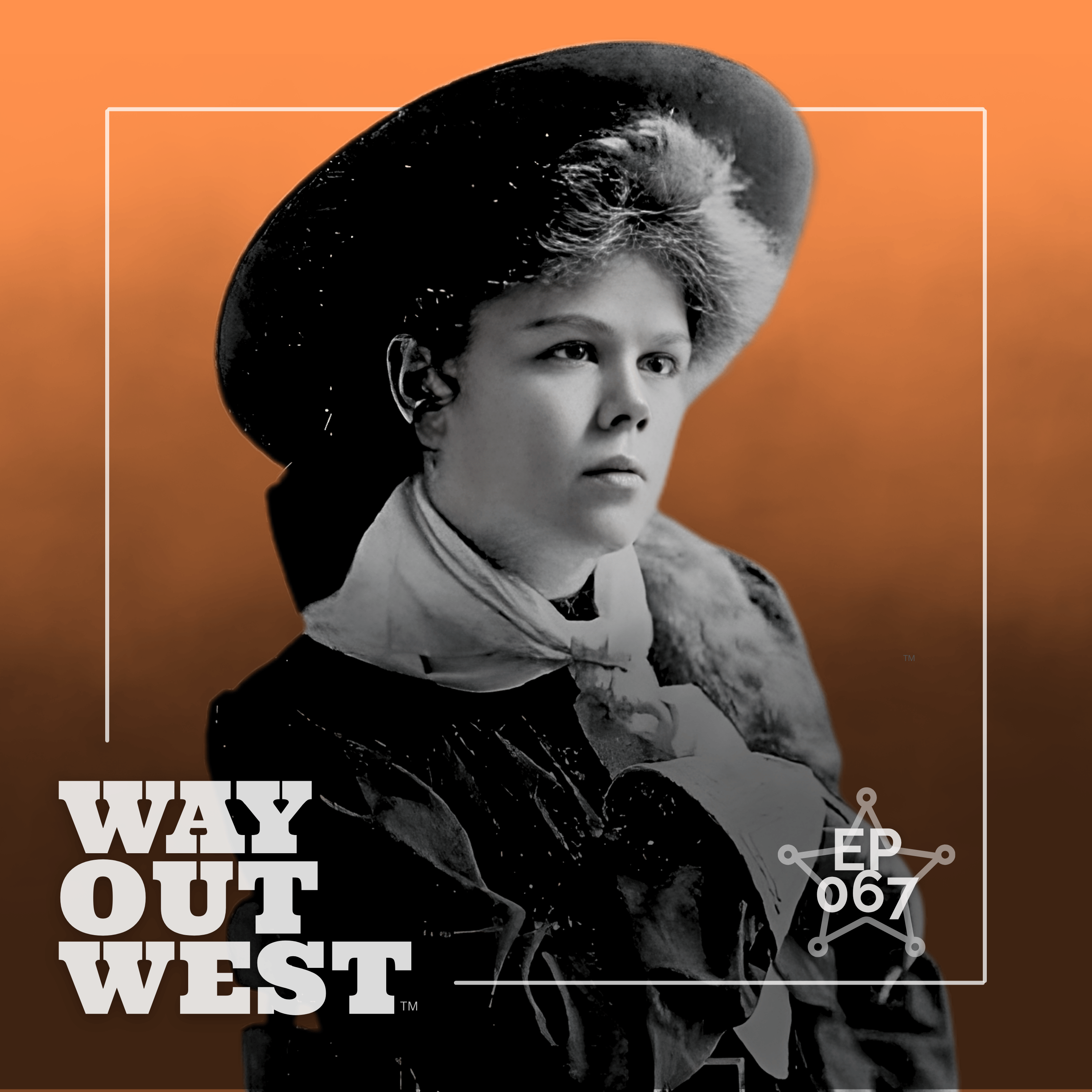

Lucille Mulhall: America’s First Cowgirl

Long before Hollywood cowgirls or rodeo queens, Lucille Mulhall rode her way into history. From the red dirt of Oklahoma to the spotlight of Buffalo Bill’s arena, she proved that true grit doesn’t wear a beard, and that the West has always made room for those brave enough to ride it.

Before there were rodeo queens or Hollywood heroines, there was Lucille Mulhall — the Oklahoma ranch girl who could out-rope any cowboy in the territory and went on to become America’s first cowgirl. Raised on the open plains, Lucille turned her family ranch skills into a national sensation, performing alongside Buffalo Bill Cody and earning the admiration of President Theodore Roosevelt himself.

In this episode, learn the story of a young woman who broke barriers in the arena and in society. From her early days chasing cattle to her rise as the star of the Mulhall’s Congress of Rough Riders, Lucille’s story is one of grit, grace, and the pioneering spirit that built the West.

What You’ll Hear in This Episode

- How Lucille Mulhall’s ranch upbringing made her a roping prodigy by age fourteen.

- The moment she beat the top cowboys in competition and became a national headline.

- Her years performing with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show and before President Roosevelt.

- How she redefined femininity in the frontier — showing that skill and courage knew no gender.

- The lasting influence of Lucille’s legacy on modern rodeo and women of the West.

Cowboy Glossary Term of the Week

Slick Fork Saddle – A slick fork saddle features smooth, rounded swells up front, giving a rider more freedom of movement when roping or working cattle. Lucille preferred this style for its agility and control — perfect for a roper who rode fast and needed a clear throw.

Further Reading

- The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture: Lucille Mulhall

- National Cowgirl Museum & Hall of Fame – Fort Worth, Texas

- Cowgirls: Women of the American West by Teresa Jordan

- Wild Women of the West by Cathy Luchetti

Enjoying the ride? Saddle up with us:

- Transcript: For a full transcript of this episode, click on "Transcript"

- Your Turn! Share your thoughts → howdy@cowboyaccountant.com

- Support the Show: Buy me a coffee → https://buymeacoffee.com/thecowboycpa

- Follow Along: Instagram → https://www.instagram.com/RideWayOutWest

03:09 - Chapter One: Born to Ride

04:28 - Chapter Two: The Girl Who Could Rope Anything

05:52 - Chapter Three: Riding with Buffalo Bill

07:24 - Chapter Four: A Cowgirl in a Man’s World

08:23 - Chapter Five: Legacy of the First Cowgirl

11:08 - Chapter Six: Tall Tales and True — Fun Facts About Lucille Mulhall

13:31 - Chapter Seven: Buster the Bull & the Cowboy Glossary Term of the Week

14:19 - Chapter Eight: Closing Reflection

[MUSIC]

Howdy. Chip Schweiger here.

Welcome to another edition of Way Out West — the podcast that takes you on a journey through the stories of the American West, brings you the very best cowboy wisdom, and celebrates the cowboys and cowgirls who are feeding a nation.

The Oklahoma wind was restless that day.

Out across the red dirt arena, a young woman sat tall in the saddle — calm, poised, her gloved hand wrapped around a coil of rope.

The crowd leaned forward on the rough wooden bleachers, squinting into the sun. They’d heard stories about her — how she could out-rope any cowboy in the territory, how her horse moved like he could read her mind.

The steer broke from the chute.

Dust flew.

In one smooth motion, she kicked forward, loop spinning, rope hissing through the air like a whistle from the prairie wind.

In the blink of an eye, the loop settled perfectly around the steer’s horns, her horse hit the brakes, and the crowd roared.

That woman’s name was Lucille Mulhall.

And that day, she didn’t just rope a steer.

She roped history — becoming the first woman in America to be called a cowgirl.

So today on the show… we’re telling the story of a ranch daughter who became a national icon, who rode in the company of presidents and legends, and who helped shape the myth — and the reality — of the American cowgirl.

After the episode, check out the show notes at WayOutWestPod.com/Lucille-mulhall.

[MUSIC]

Welcome back.

You know, every once in a while, a story rides up out of the dust and makes you stop and wonder how it ever got lost in the first place.

Lucille Mulhall’s life is one of those stories — equal parts grit, grace, and good horsemanship.

Born in the saddle, raised on the open range, and fearless in the face of anything that bucked or bolted — she didn’t just change rodeo; she changed what America thought women could do.

So, let’s head down the trail and learn about America’s First Cowgirl.

Chapter One: Born to Ride

Lucille Mulhall came into the world in 1885, out on her family’s ranch near Guthrie, in what was then Oklahoma Territory.

Her father, Colonel Zack Mulhall, was a rancher, politician, and all-around showman.

Her mother, Agnes, was known for her charm and kindness — and for giving Lucille her first pony when she was just two years old.

They say Lucille learned to ride before she could walk.

By the time most little girls were playing with dolls, Lucille was working cattle, breaking horses, and helping her father manage a spread that ran on sweat, skill, and wide horizons.

The Oklahoma land runs had brought settlers and fences, but there was still plenty of wild country left — and Lucille took to it like she was born for it.

Neighbors would talk about the girl with the sharp eyes and the quicker hands, the one who could throw a rope and stick it where she wanted every time.

Colonel Mulhall saw something special.

He started taking her along on roundup season, and it didn’t take long for word to spread: that little Mulhall girl can ride with any man on the range.

Chapter Two: The Girl Who Could Rope Anything

It wasn’t long before Colonel Mulhall started organizing local roping contests and rodeos.

At first, they were just family affairs — ranch hands showing off for bragging rights.

But when Lucille stepped into the arena, everything changed.

She rode a wiry cow pony named Governor, a horse as quick-footed as she was.

Together, they could catch, throw, and tie down a steer in record time — faster than most men.

One day in 1899, during a big event in Oklahoma City, Lucille challenged a seasoned cowboy to a roping contest.

The rules were simple: whoever tied three steers in the shortest time won.

Lucille finished her three before he got his second one tied.

The newspapers had a field day.

Headlines blazed:

“Girl Roper Beats Cowboys at Their Own Game!”

“Miss Mulhall, the Champion Lady Buckaroo!”

Lucille was just fourteen.

Her name began to spread far beyond Oklahoma.

Invitations came in — to perform at fairs, exhibitions, and Wild West shows.

People wanted to see the girl who could rope anything that moved.

And when she entered the ring, she didn’t just compete.

She commanded it.

Chapter Three: Riding with Buffalo Bill

By 1901, Lucille Mulhall had caught the attention of none other than Buffalo Bill Cody.

Cody’s Wild West Show was a national sensation — a rolling pageant of sharpshooters, trick riders, and frontier legends.

And when he heard about a young woman who could out-rope his cowboys, he sent word: “Bring her to the show.”

Lucille joined Cody’s troupe and toured the country, performing for packed crowds from Chicago to New York — and even for President Theodore Roosevelt, who was so impressed that he invited her to perform at his inaugural parade.

Roosevelt reportedly said,

“She’s the best cattle roper I’ve ever seen, man or woman.”

The Colonel — proud father and business mind that he was — turned the Mulhall family into a traveling act called “Mulhall’s Congress of Rough Riders.”

Lucille was the star attraction.

She rode trick horses, performed intricate roping routines, and took part in stage-drama reenactments — all while wearing long skirts, lace blouses, and a confidence that turned heads everywhere she went.

But for Lucille, it wasn’t about fame.

It was about proving that skill had no gender, that courage didn’t wear a beard, and that the West had room for women who could ride, rope, and stand their ground.

Chapter Four: A Cowgirl in a Man’s World

Now, keep in mind — this was the early 1900s.

Most folks still believed women belonged on porches, not in corrals.

So when Lucille Mulhall came riding out with a rope in hand and a grin on her face, she challenged more than steers — she challenged society.

The newspapers couldn’t decide what to do with her.

Some praised her as “grace in motion.”

Others tried to soften the story: calling her “the pretty Oklahoma lass with manly skill.”

But Lucille didn’t care what they called her.

She kept riding.

And when she wasn’t performing, she was back home working cattle, helping her family run the ranch. Just like rodeo cowboys do to this day.

She became the symbol of a new kind of woman — tough, independent, and proud of it.

The first true “cowgirl.”

Chapter Five: Legacy of the First Cowgirl

Lucille kept performing through the 1910s, but the era of the big Wild West shows was fading fast.

Movies were taking over, and the world was changing.

But her influence had already spread far and wide.

Young girls began taking up riding and roping, inspired by the fearless Miss Mulhall.

Rodeo competitions began to open up new categories for women.

And the image of the “cowgirl” — smart, strong, self-reliant — became a lasting symbol of the American spirit.

Many of the first generation of rodeo cowgirls — including Prairie Rose Henderson, Mabel Strickland, and Tad Lucas— openly credited Lucille as their inspiration.

Her combination of ranch-born skill, poise, and showmanship gave rodeo promoters a model for how to present women competitors to mainstream audiences.

Today, she’s often called “America’s First Cowgirl,” not only because she was first to compete publicly, but because she gave legitimacy — and visibility — to women’s rodeo.

Lucille eventually retired to ranch life, still riding, still working, still carrying herself with that same quiet confidence.

She passed away in 1940, at just fifty-five, but by then, the trail she blazed was clear, deep and wide.

She was posthumously inducted into the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas, and her hometown of Mulhall still honors her legacy every year during their Mulhall Rodeo Days celebration.

Now, I don’t know about you, I like to think Lucille would smile at all the fuss.

After all, she never set out to be famous.

She just wanted to ride — and she did it better than just about anyone who ever threw a leg over a horse.

And I think her story should be told more often. Because every little girl who’s ever backed their horse into a roping box or walked into an arena wearing a hat and spurs — she’s riding in Lucille’s shadow.

Now, I know what you’re thinking — after all that, Lucille had to have some stories worth telling around the campfire.

And you’d be right.

For a woman who rode with presidents, out-roped cowboys, and turned the American West upside down in a ruffled blouse — well, let’s just say Lucille Mulhall left behind more than a few tall tales.

So before we ride off into the sunset, let’s have a little fun.

Chapter Six: Tall Tales and True — Fun Facts About Lucille Mulhall

They called her “The Queen of the Range.”

But Lucille never let the crown sit too heavy.

Here are a few of the yarns, facts, and legends that made her one of the most colorful figures in the early rodeo world:

In one of her most famous stunts, Lucille supposedly roped a live coyote during a public exhibition — clean around the neck, horse sitting back just right.

Crowds went wild. Newspapers dubbed her “The Coyote Catcher of Oklahoma.”

And while some skeptics thought it was just a show trick, folks who knew her swore it really happened — and that the coyote walked away unharmed, just a little wiser.

Let’s see, we talked about Lucille’s favorite horse, Governor, and how he was as quick as prairie lightning.

But did you know she trained him herself, teaching him to track cattle, pivot on a dime, and read her body language?

During performances, spectators said the two looked like they shared one mind — which, in a way, they did.

Lucille once said, “A good horse is like an extra pair of hands, and sometimes a better head.”

For all her skill in the rodeo arena, she did get people talking. You see, Lucille caused quite the stir when she rode in split skirts, designed so she could rope and ride more freely.

In 1900, that was nearly scandalous — newspapers described it as “manly attire.”

But Lucille wasn’t trying to shock anyone. She was just being practical.

And, like everything else she did, it caught on fast. Before long, cowgirls everywhere were trading in side-saddles for freedom in the saddle.

And the last bit I’ll tell you about her, and I think this is pretty dang cool.

When Hollywood started making Westerns, studio heads tried to recruit her.

But Lucille turned them all down.

Seems she didn’t need a script to tell her story.

She’d already lived it.

Still, plenty of early Western heroines — from silent film cowgirls to TV rodeo queens — borrowed from her style, her swagger, and her grit.

Chapter Seven: Buster the Bull & the Cowboy Glossary Term of the Week

OK, before we wrap up this week, we’ve got one more thing.

Yep, that distinctive call from Buster the Bull means it’s time for the Cowboy Glossary Term of the week. And this week’s term is pulled right out of the tack room — “Slick Fork Saddle.”

A slick fork saddle is a style of saddle with narrow, rounded swells up front — no big horns or bulky pockets.

It’s the kind favored by old-school cowhands and ropers because it lets the rider move freely and keeps things light when handling cattle.

Lucille Mulhall rode one just like it — built for speed, skill, and control.

So next time you see one, you’ll know it’s a saddle for riders who mean business.

Chapter Eight: Closing Reflection

Lucille Mulhall wasn’t just a rodeo star.

She was a trailblazer — a woman who turned skepticism into applause, who proved that the courage of the West didn’t come with conditions.

When you picture her — dust rising, big ol loop swinging, sunlight flashing off her saddle — remember what she stood for: that true grit doesn’t know gender, and the West has always belonged to those brave enough to ride it.

Hey, if you enjoyed the show, share it with a friend who loves a good Western tale. That helps us reach more fans of the American West.

And don’t forget to follow Way Out West on your favorite podcast app, and connect with us on Instagram and Facebook.

Next time on Way Out West, we’ll take a look at how simple inventions — barbed wire, windmills, and grit — turned the open range into working ranchland. So, be sure to saddle up again.

Until next week, this is Chip Schweiger — reminding you to ride steady, keep your cinch tight, and never let go of the loop once you’ve thrown it.

We’ll see ya down the road.